|

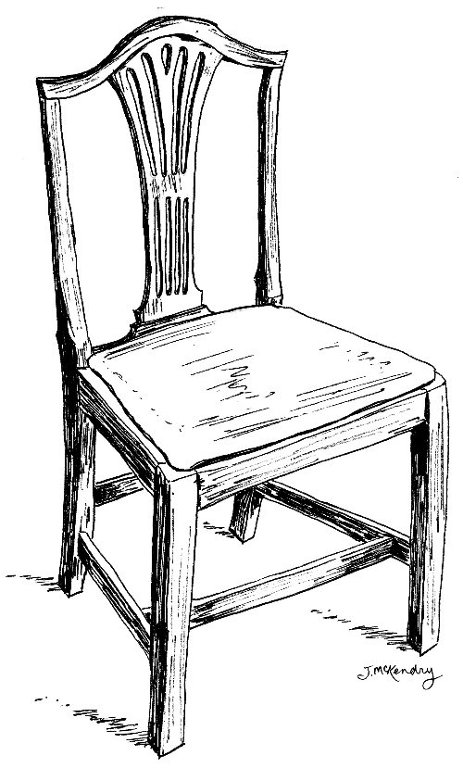

ANTIQUES: A CANADIAN CHIPPENDALE CHAIR by Jennifer McKendry©

|

|

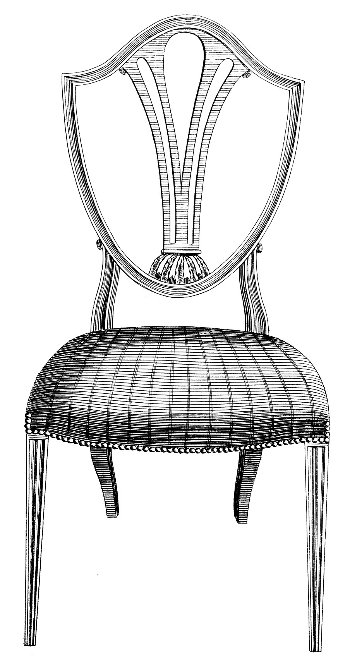

What has this sidechair, of about 1800, from Nova Scotia, in common with the famous Thomas Chippendale, who made his mark in London society fifty years earlier?

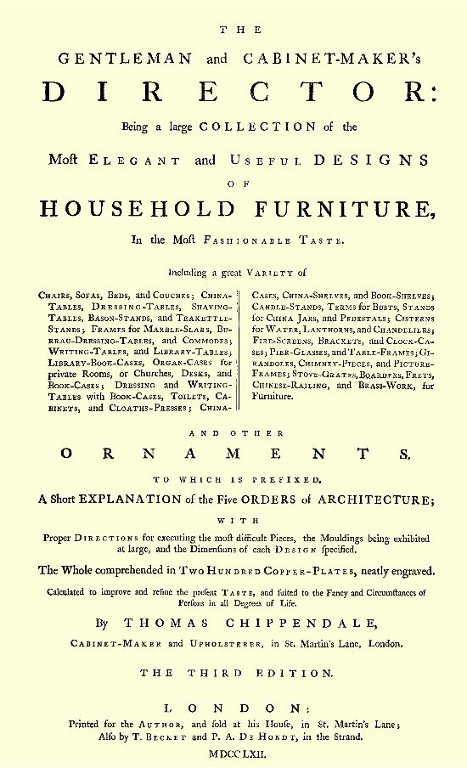

drawing and photograph by J. McKendry© Master Chippendale had the foresight to get into the furniture pattern book game in its early stages. He carefully noted the popular styles of the day, and published a book called The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director in 1754 at the rather expensive price of £2.8s. It was supported by wealthy subscribers, and meant to appeal, as the title says, to both gentlemen and cabinet-makers, “as being to assist the one in the Choice, and the other in the Execution of the Designs; which are so contrived, that if no one Drawing should singly answer the Gentleman’s Taste, there will yet be found a Variety of Hints, sufficient to construct a new one.” (Preface).

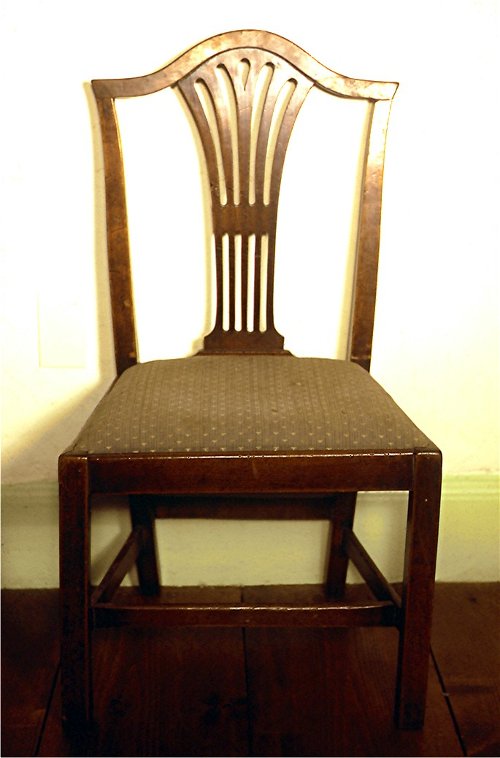

By the third and enlarged publication in 1762, Chippendale felt obliged to answer those critics who claimed that they were “so many Specious Drawings, impossible to be worked off by any Mechanick whatsoever” by saying that his own cabinet-making shop could execute them. However, this was a fairly valid criticism, as many of the chair and table designs were so fantastic in detail that they did not take into account solid structure. If one did copy the engravings exactly, the chair might be too fragile to be sat upon on a regular basis. Therefore, modifications were made even in Chippendale’s day. The further away from the direct source of inspiration, namely London, England, the more modifications that were liable to take place. So it is not too surprising that this Nova Scotia chair is not to be found in any one engraved pattern, but rather from the overall style trend. As usual there was a time lag in the colonies, and by the time this chair was constructed, circa 1800, Thomas Sheraton in his Drawing Book, 1791-94, declared that the designs of the Directors were “wholly antiquated and laid aside, though possessed of great merit according to the times in which they were executed.” Therefore, the back of the chair is out-of-fashion by British standards. The cupid’s bow line of the crest rail had been replaced by the straight back or oval. The pierced central splat no longer ran into the shoe piece, directly resting on the seat rail, but was separated from the latter by two uprights.

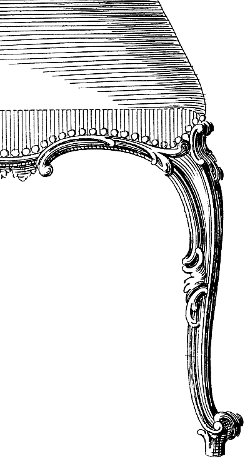

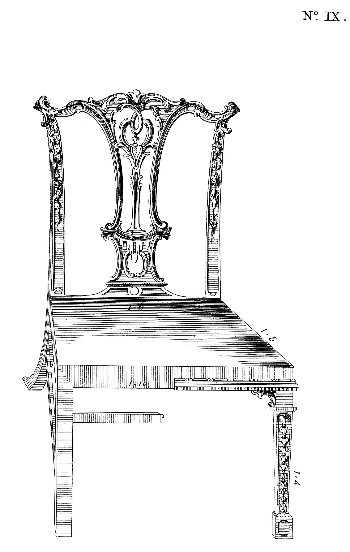

Chippendale favoured the cabriole leg and delicate scroll foot (illustrated on the left) in his book, as the most suitable to “the French Taste” (what we now call Rococo style), which was very fashionable between 1730 and 1760. However, in condescension to the incoming style of Neo-classicism, he shows other designs favouring the straight leg. These were square in section right down to the floor, although the innermost corner was chamfered off. In the Neo-classical phase of Adam and Hepplewhite, this changes to a more refined appearance through use of a taper leg and the rejection of a stretcher.

Plate IX of Chippendale (illustrated right) shows a design of a sidechair with a very similar under-structure, using no foot, and the front stretcher set back a short distance from the front legs. The pattern book chair is larger in dimensions, although the Canadian chair almost matches up to the dimensions specified by Hepplewhite in 1794. An English chair would have probably been made out of mahogany, but this one is in cherry. It is one of a set of eight, containing two later chairs, which are made in mahogany.

The

piercing on the back of the Canadian example is very simplified from the complex

interlacing in the Director. This may be accounted for by different reasons. For

one thing, the intertwined scrolls of the Rococo style were being straightened out by the

more restful, less complex, decoration of Neo-classicism in the last half of the 18th

century. This can be observed in Hepplewhite’s The Cabinet-Maker and

Upholsterer’s G

Although there were slip seats used earlier in the century, Chippendale preferred the seats to be upholstered over the rails: “The Seats look best when stuffed over the Rails, and have a Brass Border neatly chased; but are most commonly done with Brass Nails, in one or two Rows; and sometimes the Nails are done to imitate Fretwork. They are usually covered with the same stuff as the Window-Curtains.” Hepplewhite shows one chair with what is apparently a slip seat. The illustrated cherry chair has a slip seat that drops into place.

The Canadian chair demonstrates pleasing proportions and fine craftsmanship. The wood is mellow with age. Although it is interesting to speculate on its stylistic sources, it does not need to be evaluated against the more elaborate English prototypes. It is part of our Canadian culture.

**********************************************************

a Maritimes Chippendale side chair with a Rococo influenced back. Photo by J. McKendry©

top of page home page antiques (list of internal links to articles on antiques) |

uide, 1788-94

(illustrated below). Also it may have been beyond the skills of the furniture-maker

involved to carve out a more intricate design, or beyond the price range of the client for

whom the chairs were being made. And personal taste must enter the picture.

uide, 1788-94

(illustrated below). Also it may have been beyond the skills of the furniture-maker

involved to carve out a more intricate design, or beyond the price range of the client for

whom the chairs were being made. And personal taste must enter the picture.