ARCHITECTURAL DRAWINGS & PATTERN BOOKS by Jennifer McKendry copyright |

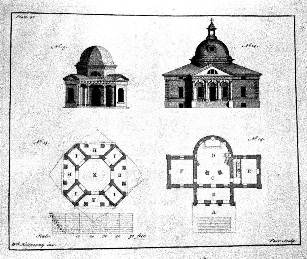

A Description of Bath, 1749, by John Wood (1705-1754), signed upper right corner by Thomas Fuller, Bath, 1855. Fuller (1823-1898) left Bath, England in 1857 for Canada, where he was the architect, with Chilion Jones (1835-1912), for the centre block of the Parliament Buildings, 1859-1866, in Ottawa. Fuller was Canada's Dominion Architect from 1881 to 1896. The following discussion about architectural drawings and architectural pattern books is taken from Town & Country Houses: Regional Architectural Drawings from Queen’s University Archives by Jennifer McKendry (1993, out-of-print): While architectural drawings (definition) were an essential part of the design process for architects and builders in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they have not necessarily been highly regarded by later generations as important historical records or attractive art objects. This is evident from the scarcity of material. An architect may have noted in his ledger that he provided more than a dozen drawings for a single project but not one has survived. The poor condition of surviving drawings - tears, missing parts, and stains are common fates - suggests neglect. Yet with what loving care such drawings were made! They were the bench-marks that distinguished an “architect” from a builder or craftsman - from whose ranks many local architects rose. As an architect prospered, he hired draughtsmen to assist with presentation and working drawings. Some were ambitious and apprenticed to become architects. It is fascinating to compare drawings with a building as constructed: the latter is sometimes an improvement at the hands of the architect correcting a flawed proposal, but there is often a loss of aesthetic appeal due to the stingy interference of the client. The identification of drawings can be a challenge. The final presentation drawings for the client are often the only ones that specify the name of the architect and give a title (usually the client’s name and often the address). A researcher may recognize the building from the drawing. But full identification involves consulting city directories, land transactions, tax assessments, maps, county atlases, insurance maps, censuses (now available to 1911), newspaper tender calls or articles, cemetery records, and architect’s obituaries and ledgers. An architect may have acquired another architect’s drawings from a client who needed alterations to or additions on his or her property. This may explain why an architect’s draft of c1857 for Edgewater, 3-5 Emily Street, Kingston ON, attributed to William Coverdale (1801-1865), survives among architect William Newlands’s (1853-1926) drawings. Newlands was considering the design of a replacement verandah in the late nineteenth-century. ? Architectural pattern books and

periodicals (definition)

were an essential component of an architect’s equipment, particularly in provincial

areas during the nineteenth century: the latest architectural trends in London, Paris, and

Boston were described and illustrated. By purchasing new or used books Kingston architects

kept up-to-date. They improved their drawing skills by copying material. An example of a

contemporary book owned by George Browne (1811-1885), well known for his 1843 design of

Kingston City Hall, is Asher Benjamin’s The Architect or Complete Builder’s

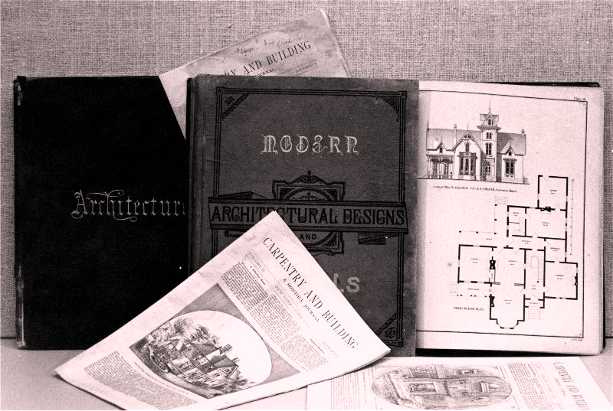

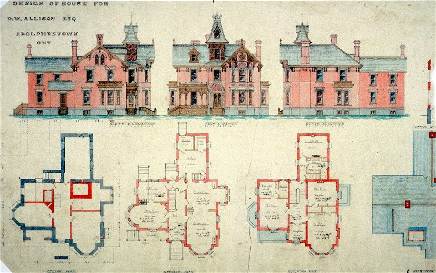

Guide (1845) published in Boston. Some publications were such landmarks that they never became outdated. Browne acquired books published a century earlier, for example, James Gibbs’s A Book of Architecture of 1739 or William Halfpenny’s A New and Compleat System of Architecture Delineated, In a Variety of Plans and Elevations of Design for Convenient and Decorated Houses of 1749. In the latter (right), on plate 20 number 15, Browne annotated in pencil a square on the octagonal plan for a summer house with four porticoes and a dome. This descendent of Palladio’s Villa Rotunda of 1570 may have attracted Browne’s attention, when he was considering the plan for John Solomon Cartwright’s Rockwood Villa of 1841 on the outskirts of Portsmouth Village (now part of Kingston). The surviving examples of Robert Gage’s (1841-post 1916) books and periodicals (below) all date from the period of his greatest activity as an architect in Kingston during the 1870s and ‘80s. As a carpenter recently turned architect he may have been anxious to keep abreast in an increasingly competitive and professional field. In the late nineteenth-century, architectural influence from the United States was very strong (indeed American architects were producing designs for Canadian buildings), and it is interesting that Gage purchased American publications by Bicknell and Comstock in addition to Carpentry and Building, a monthly trade journal from New York. Gage probably turned to plates in Cumming & Miller’s Architecture: Designs for Street Fronts, Suburban Houses and Cottages of 1871 and Bicknell’s Village Builder of 1873, when considering the design for the Allison House (now Loyalist Cultural Centre) of 1877 at Adolphustown ON.

The Allison House (now Loyalist Cultural Centre), Adolphustown, c1877, by Robert Gage. Drawing collection Queen's University Archives, Kingston

? Fortunately dedicated archives such as the Queen’s University Archives in Kathleen Ryan Hall, Queen's University, Kingston ON, are collecting and conserving architectural drawings for study and enjoyment. A selection of the Archives’ drawings of town and country houses by Kingston architects from 1822 to 1923 were shown the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston, 9 May to 20 June 1993; guest curator, Jennifer McKendry.

Home Page Top of Page Architecture (list of internal links to articles on architecture ) |