|

RESEARCHING HISTORIC PROPERTIES in the GREATER KINGSTON AREA |

|

|

|

by Jennifer McKendry© |

|

As a tenant or owner of a heritage house or

store, you may wish to learn or confirm its building date and later history.

You can pursue two avenues: hire a consultant on historical research and dating

buildings from the physical evidence or undertake the project yourself

by consulting: first, SECONDARY SOURCES. These

are written, drawn, oral, or printed sources that were created well after the

original date of your building, for example The Old Stones of Kingston

by Angus; With Our Past before Us: 19th-Century Architecture in the

Kingston Area, Modern Architecture in Kingston: a Survey of 20th-Century

Buildings, Bricks in 19th-Century Architecture of the Kingston

Area, Woodwork in Historic Buildings of the Kingston Region by McKendry; Buildings

of Architectural and Historic Significance, Kingston by the City of

Kingston in 7 volumes; County of a Thousand Lakes: the History of the

County of Frontenac 1673-1973 edited by Rollaston;

or Kingston: Building on the Past for

the Future by Osborne & Swainson. (For a

full bibliography and chronology of the region’s architecture bibliography and chronology - please use BACK on tool bar to return to this page.) The most reliable secondary sources contain notes

(usually at the bottom of the page or at the end of a chapter or the book)

that cite the primary sources used by the author. The least reliable secondary

sources have not used primary sources, but have taken information from other

secondary sources. Errors are thus perpetuated or even increased, yet

the writing tone may sound very self-assured. Always take secondary

sources ‘with a grain of salt.’ Always read endnotes or footnotes

carefully (check the index for additional topics not covered in the text but

included in the notes). Look for the publishing date, and start by

reading the most recent book or article on the subject, and then work your

way to the oldest published material. Write down or record what books you

have consulted (author, title, publishing date, call number, which library),

and whether or not they contained useful information -- on 4 x 6 inch ruled

index cards. If you should set this project aside for a time, it is difficult

to remember later what you did or did not consult. Or what initially

seemed like useless information (on the historical period or the

neighbourhood but on not your house) may take on a new and useful slant at a

later stage in your research. Look for secondary sources in municipal

libraries, college and university (Stauffer Library and Special Collections

in Douglas Library) libraries, and new and used bookshops. Ask about

inter-library loans if necessary. Don’t forget to look for articles in

journals, such as Historic Kingston (the Kingston Historical Society

index https://search.digitalkingston.ca/islandora/search/?collection=historic off-site link); Foundations,

the newsletter of the Frontenac Heritage Foundation; and the Journal

of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada www.canada-architecture.org/journal.aspx for old issues (off-site link). Make notes of oral history, but remember that

people’s memories generally only extend into their grandparents’ generation,

and that there is often considerable error in memories. On the other hand,

they can contain a kernel of truth and give an interesting human slant on

events. second, PRIMARY SOURCES. These are written, drawn or printed sources of

information that are more or less contemporary with your building, for example,

maps, tax assessments, newspapers, censuses, architectural drawings,

photographs, diaries, etc. In general, it is desirable to have at least two

primary sources to validate facts. Sometimes the research game seems like

doing a puzzle and, eventually, all the pieces fall into place -- if you are

on the right track. BEGIN AT HOME Assemble as much information as you already have from

secondary sources, and take it with you to the archives, land registry office

(in transition, check on location), or where ever you are going to do further

research on primary sources. Minimally -- before you leave home -- you

should start your search with the building’s street or rural address, town

lot number or portion of (ie -- north-east corner

town lot number 21), and farm lot number (ie --

east half of farm lot 12, 4th concession, Storrington

township). Make note of the full names of any owners or tenants and the dates

they were associated with your building (you may only know yours and the

person who sold you the property). How to find this information:

your property tax forms, your purchase of property records, and county

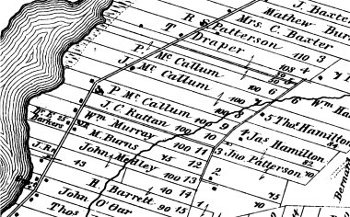

atlases (many have been reprinted, see local libraries) such as Meacham’s Illustrated

County Atlas of Frontenac, Lennox & Addington Counties, 1878,

reprinted 1972. A copy of any map showing your lot is helpful when you

are working on site, and when you are explaining your interests to staff or

for yourself when puzzling out bits of information. Google your address

or names of persons in case the web can provide information. Someone, for

example, may have posted helpful information about an ancestor, who may have

once owned your property. County atlases have been posted on line, as well as

censuses and certain newspapers. NEW!!

Land registry records online https://www.onland.ca/ui/13/books/browse/1?per_page=30&page=1

(this takes you to the various books but you can also go to the Home page.

Keep track of the page number at the bottom of the screen, when you find

relevant material, in case you need to consult it again (an example is 589 of

1919). There is a very large number of pages in each

book. Gather supplies to take with you: including pencils (archives usually only permit

pencils), notepaper and change for photocopy machines. Increasingly,

some prefer to record on laptop computers and other electronic devices. You

may want to take your own photographs of documents, usually flash is not

permitted. You can also order photographs at the archives – check on the

cost, which periodically changes. A memory stick may be needed to save

material found on microfilm. WORKING AT THE

RESEARCH SITE Record or write everything down, by topic (tax records, city

directories, family stories...), on index cards. Each card should have

a concise heading on top, including the date of the material noted.

Don’t forget to make a note of which documents you consulted that were not

helpful (... nothing in 1861 census, nothing in 1871, can’t find 1881 census

....). Write down the sources for all information. Make

photocopies or take photos (flash usually not permitted) whenever possible

(don’t forget to write the source on each). If possible, record on a memory

stick material found on microfilm. Land registry records You can now

consult abstract indexes at home online https://www.onland.ca/ui/13/books/browse/1?per_page=30&page=1 (off-site link) or on microfilm at the research site Many original

documents (land registry books or "index"), microfilms of the

indexes and bound copybooks of the instruments at the QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY

ARCHIVES (second floor, Kathleen Ryan Hall, 613-533-2378 http://archives.queensu.ca/databases.html off-site link). They also

have land information for areas beyond Greater Kingston – it is worthwhile

inquiring. If

you are having problems knowing which registry book to use, look at the

archives’ large wall map, which is coded to work with a separate key to the

various subdivisions. Once you exhaust the information in a particular

registry book, look at the bottom of the last entry for the directions to the

next book and page ("index 3 folio 465"). You may end up using several books if the

information on your lot is scattered. You may find it easiest to begin in the

abstract book with the most recent entry on your property -- your acquisition

is likely filed under the farm lot and town lot numbers by township, town,

village or city. Then work back in time tracing by owners (write it all

down!), until you get as far back as possible -- possibly to the 1790s with

the United Empire Loyalist grants (your property may only be a very small

portion of the original grant). Buildings usually do not appear in land

transaction documents, unless they are particular landmarks or designate land

boundaries, for example, the building’s eaves overhang adjacent

property. They may, however, be mentioned in wills as legacies (wills

are sometimes included in land registry records). You cannot assume

that the first (or even later) dated recording of your property means that it

included your buildings. It may have been vacant land or have contained

a structure that has disappeared and predated your building. Now assess the most likely clues for improvements to

vacant land: jumps in purchase prices (“B & S”), heavy mortgages

(to build or to extend or to modernize), subdividing of the land (1/4 or

1/5 acre lots created out of larger acreages). After you have narrowed

down a possible building date (rural properties provide the fewest clues), it

may be worthwhile pulling and reading some of the documents, in case a

building is mentioned (“the leasee must build in

the same material as the existing adjacent brick building owned by the leasor....”). Wills are particularly promising

and may, at the least, reveal familial relationships with married daughters

or with granddaughters or widows who have remarried. Some properties

which seem to have changed hands frequently may actually have remained in the

same family for generations. You now have a list of names associated with the

property, and a possible building or improvement date. These are helpful as

you search further. Tax assessments. The City of Kingston (earliest

1838), Village of Portsmouth, and Township of Kingston (in general, much of

the latter’s early records have not survived) records are at the Queen’s

University Archives. Start with the approximate date you found in the land

records plus the list of names. The city records are organized by wards

(see Meacham County Atlas of 1878, your voting notice, or maps at the

archives. The ward boundaries & names change with time). The

records may have an alphabetical listing of surnames and/or the assessor may

have gone from house to house on the street. Write down all the

information on your property, and look for hastily added notes, such as

“being built.” You may discover the ages and occupations of the tenants

and owners. In general the assessments reflect the conditions of the

previous year. You may need to read for a number of years to establish

a pattern. Was the property assessed at $50 from 1870 to 1879, and then

suddenly increased to $150 in 1880? This likely indicates a building

was erected at that time. Was there a further jump the following year and

then that amount stabilized? This may mean that there was a transitional

year, in which the building was only partly built and thus taxed lower than

when the building was finished for a full year. Occasionally, there is very

useful information on the house’s materials, number of storeys, fireplaces,

and tenants.

PUGH

HOUSE 1

Baiden Street, Kingston ON, 1860. The building date for this frame

house in Portsmouth Village was confirmed by a note added to the 1861 census

that the house was “nearly finished, 2 stories, frame,” in addition to a

frame house of one-and-a-half storeys that had appeared on the 1851

census. Voters’ lists, tax assessments and appeals, directories, land

records, and other primary sources filled in the history of the Pugh family

who owned it until 1901. Drawing

by Jennifer McKendry© Voters’ Lists can also be useful. Censuses (on microfilm

at many provincial, national archives and libraries or use in Documents in

Stauffer Library). These were taken every 10 years, and are now

available to 1921. They are organized geographically, hand written, and

frustrating to use, as you search for names. They are divided by wards

within the city. It is worthwhile to check if someone has redone them

with alphabetical listings of names (see especially the genealogical section

of the Kingston Public Library). Especially helpful are the searchable

versions on the Library and Archives Canada website, www.collectionscanada.ca (off-site link). You may want

to double-check the original census, in case the transcriber missed useful

material. Here you may find the ages of the tenants or householders

with their families, where they were born, religion, occupation, acreage

owned, pets, animals, and sometimes the material and number of storeys in the house (the latter is true of the 1861

census). Check for added notes such as “half finished,” if the building was

just erected or being erected during the census-taking. Agricultural censuses

for rural properties can provide interesting details about a family’s assets. Directories. There were annual business and personal directories,

beginning in Kingston in 1855, and found in local archives and libraries (see

Kingston Public Library and Special Collections in Douglas Library - the runs

are incomplete in both locations). Often the city, neighbouring villages, and

rural areas were included in the same directory. They may be organized

by street and/or alphabetical (more or less) lists of surnames, usually

accompanied by occupations. Street numbers are not very helpful, as they

were subject to change. Does the family name you found in the registry

office suddenly appear in the directory listing for your street? This

may confirm that your building was erected at that time. Many directories are

now in a searchable form on the web. http://archive.org/search (off-site link). In the late 19th

century, many street numbers correspond to today’s.

If your house, for example, is 82 Smith Street and such a number is not

listed in the directories of the 1880s (the numbers 78, 80 and 84 are there).

But suddenly 82 appears in the directory for 1890

and this means you can assume your house was built at that time. One way to

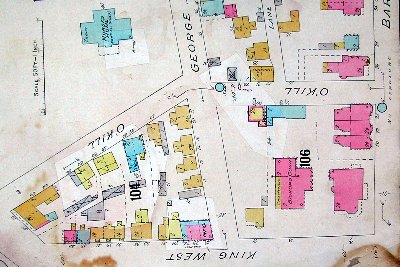

check street number changes is in the 1892, 1908, 1924 fire insurance plans.

Sometimes the old street numbers are crossed out and the new ones written in. Newspapers. Kingston papers begin in 1810, and are on microfilm in the

Kingston Public Library and in Stauffer Library. They are frustrating

to use, unless you have a specific date in mind. Kingston papers are

indexed from 1810 to about 1850 in the Kingston Public Library -- now

available on line at www.digitalkingston.ca (off-site link). Some entries have the actual wording of the newspaper

article. Try http://ink.ourdigitalworld.org/ for newspapers running to 1900. It uses OCR

for searching and may mess up words because of poor quality printing. You

need to be patient using it. Put in the word you want to search, such as

Sydenham; then narrow down the years, such as between 1875 and 1900; then

pick a Kingston newspaper such as the British

Whig or Kingston News. If a

very large number of hits appear, perhaps try the most promising year first

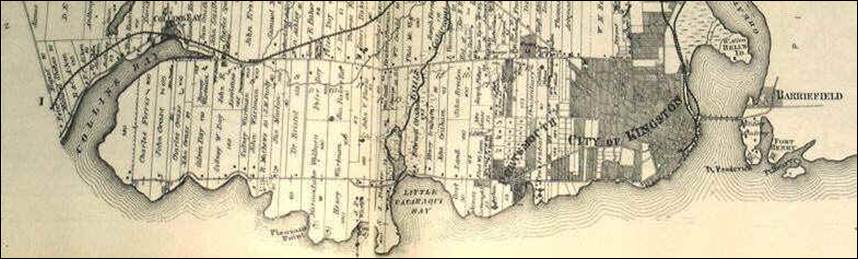

or patiently go through all of them. Maps. Many maps do not contain specific information on individual

buildings, but can be helpful in locating your lot. There are numerous

original maps in the National Map Collection of the Library & Archives Canada

in Ottawa, and certain of these have been reproduced and can be consulted in

Maps (Stauffer Library) and Special Collections (Douglas Library).

County atlases from the 1870s and ‘80s are useful - don’t forget to look for

lists of names and for views of houses (remember your house or store may be

listed in the table of contents under the name of whoever owned it at that

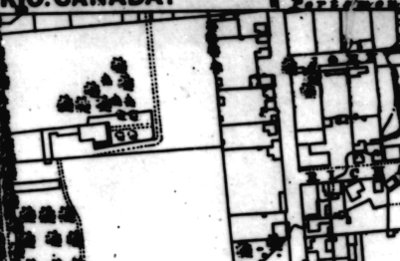

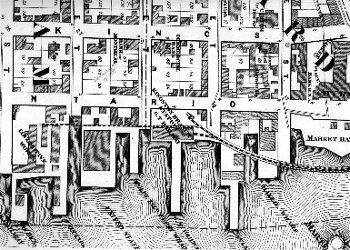

time). There are certain maps that contain information on buildings, such as

the very detailed 1869 Ordnance Maps (showing verandahs, landscaping,

outbuildings, fences, paths) and the Fire Insurance maps of the 1890s into

the 20th century (see Special Collections and the Kingston Public Library).

The insurance maps tell you about materials, number of storeys, additions,

and some alterations as you track the building over several years. The

city website has some maps and aerial views available at

https://www.cityofkingston.ca/explore/maps/historical . To get a

handle on how your building fits into today’s maps see https://www.cityofkingston.ca/explore/maps/kmaps -- this can be

useful to compare with historical material.

1869 Ordnance (King W. at Mowat) :

1865 Innes (Ontario St near City Hall)

1875 Brosius

(Queen, Ordnance, Montreal)

1878 Meacham atlas (hwy

15, Gore Rd)

1908-1911 Fire Insurance (King W, Okill, George, Barrie). Colour coded: pink for brick,

yellow for frame, blue for stone, grey for sheds line Architectural Drawings, Accounts,

and Tender Calls.

Everyone hopes to find this sort of material

which reveals so much about your building’s origins, but such a find is

exceptional. There are collections of drawings in the Library & Archives

Canada in Ottawa (of particular interest to Kingston is the Power & Son

collection, although only a small percentage predates 1900), Archives of

Ontario in Toronto, and some municipal and university archives and libraries,

as well as private collections. In Kingston, try the Queen’s University

Archives (Kingston Architectural Drawings including the Robert Gage drawings,

Newlands drawings, Clugston drawings, etc.). The

vast majority of buildings originally had such drawings, but they have been

lost or are unavailable due to neglect, fire, private collectors, and so on.

Tenders call by the architect for masonry contracts etc. are difficult to

find in the newspapers, unless you have a reasonably narrow range of dates to

search. There were no published tender calls for many buildings. Photographs and other views. Drawn,

painted, or photographed views that include your building can be very

interesting to show even minor changes (bring or borrow a magnifying glass).

They should be examined regardless of date. Alterations may have occurred

only ten years ago. Ask around the neighbourhood, try to find the former owners

or tenants (snaps of children may reveal, in the background, details about

the house’s front door, etc.), write a letter to the editor of the local

newspaper or historical society or foundation newsletter, look at the picture

collections in the local archives (in Kingston, Queen’s University

Archives) or libraries, provincial (www.archives.gov.on.ca off-site link - search the collections – visual database) and

national archives (www.collectionscanada.ca off-site link - research – photographs) Once you’ve exhausted the

identified pictures and postcards, try the category of unidentified houses or

stores. Check also under overall street and aerial views. Look through

the many tourist and promotion booklets and postcards published in the late

19th and early 20th centuries in the collections of municipal and university

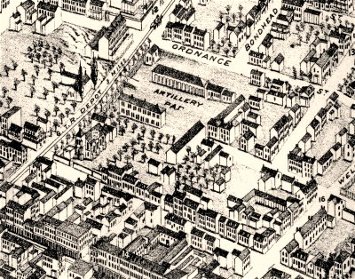

libraries. Bird’s-eye views of towns and cities, published in the 1870s

and ‘80s, can be very informative, for example Brosius’s

view of Kingston in 1875 (detail above). Many

have been reproduced. Many have been

reproduced. Aerial views (Stauffer Library, Queen’s U.) sometimes help but

may not provide enough details or tree cover may obscure your building – good

for rural layouts of large properties. Check in Early Photography in Kingston from the Daguerreotype to the Postcard

(2013) by McKendry. Municipal or Township minutes, building

permits, etc. These are a long shot, but your building might be mentioned

in connection with road infringements, digging sewers, placement of privies,

tax appeals, etc. It is difficult to know what dates to search.

Building permits are a fairly recent aspect. In Kingston, early city,

township and Portsmouth records are held in the Queen’s University

Archives. One can always hope to turn up information in diaries and

personal papers, but it is hard to know where to start, unless your

research has given you leads. Wills are the most productive. Genealogical information While this may not

add to the information on your building, it will create an appreciation of

the original owner as architectural patron. Certain aspects will have

already been noted, as you looked in the censuses and tax records.

Birth and death dates may be available at local cemeteries (Cataraqui

Cemetery, St Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery) and through recent cemetery

recordings, often published by genealogical societies (see Kingston Public

Library) in helpful alphabetical order. Probate

records,

organized by the family's surname, can provide very helpful inventories of

material goods, if an estate underwent probate. See various archives for

microfilmed records. Inscribed dates. Check carefully over all

interior and exterior parts of the building for an inscribed building date,

possibly located in an unusual location such as a chimney stack. Assess

whether it was made at the time of building or added later (and thus may be

incorrect). Assess whether it actually refers to the building's construction

or is a commemorative date particular to an individual or a family. Don't

assume a coin of an early date that is discovered in a partition etc.

coincides with the date of the building. STYLE AND CONSTRUCTION. Now

that you have acquired information from primary and secondary sources, assess

your findings against the style and construction of your building. There

is always the possibility that your house is a replacement for one lost by

fire or demolition. There are various books and articles on style and

construction in libraries and bookstores. In addition you may need to

take courses or call in a consultant. For an article on this website. click on style (return here by the 'back" button on your tool

bar). ***************** Jennifer

McKendry, an

architectural historian and a consultant, is the author of With Our Past

before Us: 19th Century Architecture in the Kingston Area

(1995), Modern Architecture in Kingston:

a Survey of 20th-Century Buildings (2014), Bricks in 19th-Century

Architecture of the Kingston Area (2017) and Woodwork in Historic

Buildings of the Kingston Region (2018). ***************** MISC. For individual architects, try http://dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org/architects/search?alphabetical=a&name=power city

directories http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=collection%3Akingstonfrontenacpubliclibrary&sort=-publicdate ship

passengers biographies

of well known Canadians Canadian Architect & Builder 1888 – 1908 http://digital.library.mcgill.ca/cab/search/browse_frameset.htm articles in

the Journal of the Society for the

Study of Architecture in Canada 1980 – 1999 |

|

"An interesting piece

of use to many. Any merit in including Lands and Surveys reports,

note-books etc? While concerned with initial laying out of places, often re-surveys contain accounts of

existing properties and activities. In the reference to probate materials, you may wish to

point out that both the will and the very valuable inventories may

refer to property." B.S.O. "McKendry's excellent

article detailed the process of researching historic properties; perhaps your

readers should have been cautioned that personal research is extremely

gratifying, even addictive. Alternate sources for additional details include

the Archives of Ontario computerized Land Record Index, a microfiche

set, which can be found in many Ontario libraries. This tool is a compilation

of all the provincial records (including Land Rolls) predating the Crown

patent. Two indices are presented: one by name (check alternate spelling) and

the second by Township/Town, lot & concession. Also, the Upper Canada

Heir & Devisee Commission I & II - numerous Kingston-area

properties had been exchanged or inherited before the Crown patent. The

commissions of 1797 and 1804 are available on microfilm at Queen's University

Archives. The latter also has the Kingston and Quinte

regions microfilm on Township Papers that usually, but not always,

predates the Crown patent. The papers of a township were filed by

township lot & concession. However, the papers of a

town are filed alphabetically by the name of the owner," T.S. Comment by the author: Some

of these sources are not likely to help you date a building (the vast

majority of buildings in this region date post the War of 1812) but may

provide important information on the history of the land itself. Home Page

Top of Page

Architecture (list of internal

links to articles on architecture ) |