|

STYLE by Jennifer McKendry©

Classical pediment of the Gildersleeve House, c1830, photo by Jennifer McKendry © |

|

ARCHITECTURAL STYLES can be a handy tool to understand heritage buildings, but it is only one of many. It is also important to look at such determining factors as technological innovations, building materials, demands of the site, interior plans and functions, the purpose of the building, the historical context, the characteristics of an individual architect and/or designer, and the social aspirations of and restraints on the owners. It is convenient to give dates for the beginning and end of a style but this may give a false impression as there may be no exact start-up date and no exact termination; for example, one could argue that the classical style has been around since the Greek and Roman era and has yet to disappear, particularly with Post Modernist style. It has periodically undergone such significant modifications - for example during the Gothic period - that it seems at times unrecognizable and yet the use of the Orders may survive in a modified form as the capitals of compound columns in a soaring cathedral. In a Kingston heritage building, classical proportions and rhythm may be the principle behind how a building is organized into storeys, ratio of height to width, and how the windows and doors are placed into the walls; yet the building may be severely plain or vibrantly ornate because of Gothic ornaments. Nonetheless, one can generalize and note that Gothic ornaments did not make an appearance in the Kingston area until the mid 19th century (and yet were in vogue in Britain from the late 18th century) and that a complex eclectic style was not seen until the 1870s. It is helpful to know that one would not date an ornate house with certain features as originating in the 1830s, but begin one’s search for its building date after c1870. This can be important, because family and oral tradition may place a building close to the date the land was acquired or take the date of a building formerly on the site and apply it to a replacement structure. (See also the article on this website "Researching Historic Properties in the Kingston Area" - please use "back" command on top tool bar to return to "Style" article) We are seduced by the thought that, the further back in time we can place our building, the more interest it has. This undermines the value of the building, as it relates to whatever time period saw its conception. It’s all interesting! Late 19th century and 20th century structures are only now being appreciated in the Kingston area (see Jennifer McKendry, Modern Architecture in Kingston). Compare the contents of volume one of Buildings of Architectural and Historic Significance, written in 1971 and containing only buildings that predate 1865, with volume six, written in 1985 and containing many later buildings running into the 1920s. Or Margaret Angus’s The Old Stones of Kingston of 1966 describing buildings before 1867 with Jennifer McKendry’s With Our Past before Us: Nineteenth-Century Architecture in the Kingston Area of 1995 describing buildings to 1900. To own a house built in the 1880s is to visualize a context of the country struggling with unity issues, the completion of the railway across Canada, the North-West Rebellion, the establishment of a national art gallery, the excitement of the French avant-garde art movements such as neo-Impressionism, the growth of skyscrapers in the United States, and the spreading influence of the Beaux-Arts movement in Canadian architecture. The 19th century was basically split between classicism and medieval revivals. Classicism, derived from the Greek and especially the Roman periods, was reworked in the Renaissance and Baroque, and manipulated by the Neoclassicists in the late 18th century. A new enthusiasm in Britain and the United States was developed for Greek art and architecture in the 1830s but had limited appeal in the Kingston region. During the 1870s, Empire style, which derived many of its forms from the French Renaissance, gained ground locally. Towards the end of the 19th century and well into the 20th, a love for classicism was rekindled with the studies of Canadian architects at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, as well as the growing influence of American architects interested in that style. By the mid 19th century an alternative style, Gothic Revival, competed with classicism (which continued to flourish). Gothic looked back to the medieval British, French and Italian eras. By the 1880s, Romanesque Revival was gaining favour, at the same time as a number of these styles converged into an eclectic style, sometimes labelled “late Victorian.” It is thus apparent that the difficulty with “Styles” is that there is much merging of characteristics and overlapping in time. The use of the names of British royalty to signify stylistic periods such as “late Georgian” deepens the confusion. Architects had to be well versed in all these styles and be prepared to turn out classical designs as readily as medieval ones. As the 19th century gave way to the 20th century, there was a vast repertoire of styles available. Gothic Revival continued, particularly for religious buildings and educational institutions. Its old rival, classicism, gained new strength as “Beaux-Arts.” There were also Arts & Crafts, the Chateau Style and Queen Anne. It’s not surprising that modern architects reacted by rejecting ornament and historicism (which often hid or obscured structural materials) in favour of honesty in materials and forms. The strength of steel permitted wide expanses of “weak” areas that could be filled with sheets of glass. Solid walls began to shrink and buildings shimmered with transparency. Reinforced concrete allowed walls surface to swell and recede, sometimes making a building more like a rounded sculpture than a box. Boxes, on the other hand, were created with flat roofs and machine-like qualities. Pre-fabrication threatened the individuality manifested in earlier buildings, which had received so much hand-crafted treatment. EXAMPLES The Lines House, late 18th century, once stood on Ontario St at Earl, Kingston, but was burnt after it was moved to a new site in 1987. At first glance, this frame building seems to lack a “style” but the controlled placement of openings and general proportions were influenced by the rational qualities of classicism. Photo by Jennifer McKendry ©

Summerhill, on the other hand, is extremely “classical” in the tradition of the Palladian Villa, which can be traced back to the 1570s work of Italian architect Andrea Palladio. He was fascinated by the surviving buildings of the Romans, as is portrayed in his book, The Four Books of Architecture. Summerhill was built and possibly designed by its owner, the Reverend George Stuart, in 1836 opposite the Kingston General Hospital. Part of Queen’s University since 1853, it was originally a private house featuring a central block flanked by lower connecting wings (now rebuilt) and end pavilions. Tuscan colonnades reinforced the classical qualities of symmetry, beauty and harmony. Early photo on left, Queen's University Archives; Photo on right with restored porticoes by Jennifer McKendry ©

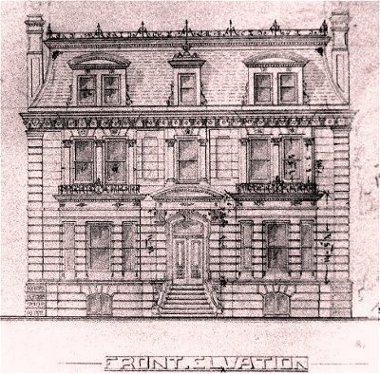

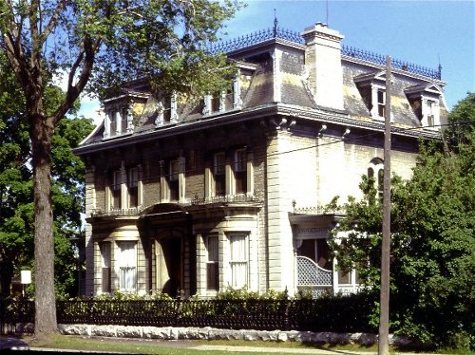

Pugh House, built in 1860 for the owners, Mary and John Pugh, in the village of Portsmouth, is an example of the long popularity of classicism – here demonstrated in the symmetry and regularity of this frame house. Classical ornament is restrained: there are of dentils on the doorway entablature supported by pilasters. Pugh, a cordwainer, taught the trade of shoe-making at the Provincial Penitentiary. Photo by Jennifer McKendry © The Empire style relates to classicism, as seen in the symmetry, central focus and detailing of Kent House, 85 King St East, built c1877 for Rybert Kent by architect John Power. Classicism is applied with a heavy hand. An Empire roof is typically mansard - a roof with a double slope. The lower slope is tall and steep-pitched. The skyline is often accented by an iron fringe. There are usually dormers to light the attic – now good habitable space because of the gain in head-room due to the steep pitch of the roof. Architectural drawing of Kent House by Power c1877, Queen's University Archives, Kingston

Empire style: 85 King Street East, photo by J. McKendry© In the early 20th century, there was a conscious effort to remodel classicism under the Beaux Arts or Colonial Revival style, as seen in the Architect’s Office, 258 King St East (below), built in 1909 for the architect Henry P. Smith. Classical detailing is lavishly applied in this small concrete building finished with roof tiles. Photo by Jennifer McKendry ©

Gothic Revival can be applied with a light hand, as characterizes Elizabeth Cottage, the home and office of architect Edward Horsey, built in 1846 at 251 Brock Street. Pointed arches, finials, verge boards, bay windows, oriole windows, and hood mouldings give a pleasant contrast to surrounding classical buildings such as 247-249 Brock Street of 1842-3. Photo showing the addition of 1883 (on the left) by Jennifer McKendry ©

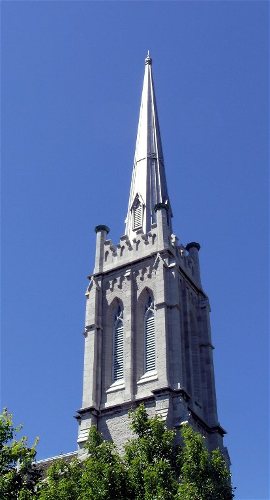

Photo on upper left, tower of Sydenham Street United Church by Jennifer McKendry © Photo on right of St Mary's Cathedral by Jennifer McKendry ©

Romanesque Revival provided an

alternative style for churches as the 19th century drew to a close.

Joseph Power designed a striking composition for St

Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in 1888 on a corner lot at Princess

and Clergy Streets. Heavily textured stone and massive round arches create a

sense of power. William Newlands choose this style in 1892 for Victoria School on Union Street.

Early drawing of St Andrew's

photo of Victoria School by Jennifer McKendry ©

Photo by Jennifer McKendry ©

Architecture (list of internal links to articles on architecture ) |